”As scholar and curator Elsa Peralta notes, after over five centuries of holding power over colonies, the end of the empire and the democratisation of the country did not erase Portugal’s self-image as an imperial nation. The national narrative still revolves around symbols of Portugal as an imperial maritime entity, and ideas of the Portuguese “as peaceful, non-racist, gentler colonialists, and of their culture as universal, hybrid, somehow Creole, enriched by centuries of colonial contact.”1“

“Portugal’s colonial exhibitions took place in 1934 and 1940, the first in Porto and the second in Lisbon.”

"An idea of empire built upon the notion of the Portuguese as a marine folk, descendant of the “heroic discoverers of the world”, held by fate to the higher call of helping others “reach civilisation”—through colonisation. This rhetoric rendered invisible the violence of Portuguese colonialism, by inscribing the idea of a softer, miscegenated and multicultural colonialism.2 The exhibitions contributed to forming and disseminating these ideas, by creating a strong communicational apparatus that merged the political and the aesthetic to embed a sense of national identity tied to the discoveries.”

“The exhibition in Porto took place in the iron and glass structure of the Crystal Palace, transformed with a fake art-deco facade, topped by statues of an elephant and a lighthouse. Inside was a series of exhibits addressing Portuguese expansion since 1415. In the gardens, there were replicas of monuments and villages in which inhabitants of the several countries of the colonies—brought to Porto—were exhibited while living in a simulation of their habitats. The colonial exhibition of 1940 in Lisbon sought to reaffirm the extension and importance of the Portuguese empire and was meticulously planned to become a large and festive party. Taking place in the capital, it was much bigger in scale, with the renovation of a whole area of the city, repositioning Lisbon as an imperial city. Again, it included simulated habitats, and highlighted the Portuguese project of civilisation, now strongly tied to the narrative of the Portuguese discoveries and ideas of luso-tropicalism.” (Marcas de Lusotropicalismo no Marcelo)

“Their story speaks to Portugal’s difficulties in dealing with its past, due in great part to how the regime succeeded in communicating a sense of Portuguese identity based on an idealised version of history, which in its persisting memorialisation renders invisible the people affected by them, in a country with enduring and widespread racism and deep inequality.”

Porto - Portuguese Colonial Exhibition

"The First Portuguese Colonial Exhibition took place between 16 June and 30 September 1934 in the gardens and Crystal Palace in Porto. The exhibition contained 400 pavilions and took 5 months to build, and was supported financially by local businesses and the church, which organised excursions to the event and were represented in the exhibition and its advertising. (...) In the gardens, visitors could “travel around the world”, by foot, train or cable car, through streets with names alluding to Portuguese colonies, and reproductions of monuments such as the Arch of the Vice-King of India, or the Macau lighthouse. A theatre, zoo, tea house and several monuments were created for the event. Inhabitants from the colonised countries were brought to Porto to live in an environment constructed to simulate their “real” habitat—a highlight for the public."

“The idea of a “Portuguese Empire” was established by law in 1930: the “colonial act” stated that the Portuguese domains across the seas would be denominated as colonies and that “the organic essence of the Portuguese Nation was to play out the historic function of possessing and colonising overseas domains, and civilise the indigenous populations found there.””

"The exhibition received 1.3 million visitors and largely contributed to the construction of a colonial narrative by setting up a communication apparatus that showcased the empire not “through words alone, but through live, animated truths. For example, by presenting “villages” in which inhabitants from the colonised countries—brought to Porto—were exhibited while living in a simulation of their habitats, creating stereotyped visions of “the other” by presenting these people as “primitive” and incapable of contributing to a civilisational process."

"According to Vicente, the exhibiting of people from the colonised countries represented “colonial spaces that emerged as feminized, made of disorderly nature that the imperial European masculinity would control”—eroticising the empire, made highly seductive and available, in its appeal to “become colonized” and obscuring inequalities of origin, gender and sexuality."3

“The Portuguese Monument to Colonial Effort was commissioned as an ex libris of the exhibition, occupying an important place on the Square of the Empire, in front of the main entrance to the Palace of the Colonies. (…) it was ten metres tall and composed of a pillar surrounded by six parallelepipeds at the base, all presenting a figure “personifying Portuguese colonisation”. Each of these figures was naked and carried a symbol on its torso: the warrior the sword; the missionary the cross; the merchant the caduceus; the doctor the serpent and the cock; the farmer the ear of wheat; and the women prominent breasts.”

“In 1984, ten years after democracy was installed, and half a century after the first colonial exhibition took place, the monument was reassembled under the orders of the then city councillor and former settler, Paulo Vallada.”

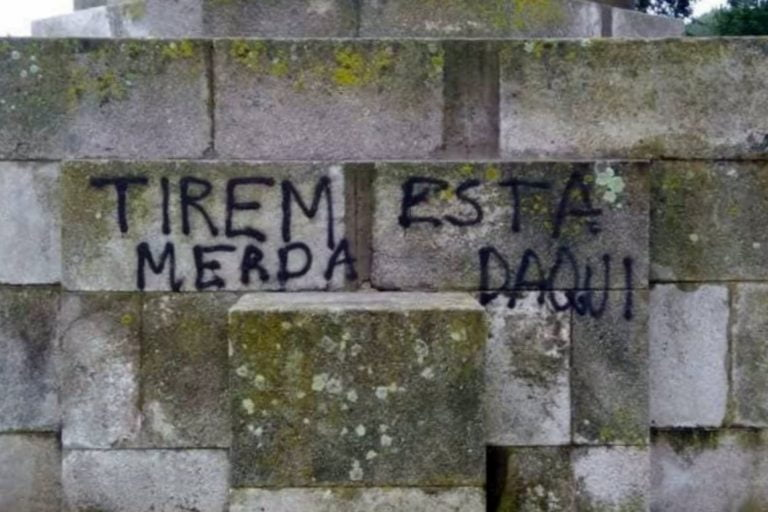

“Collection of graffiti on the monument in recent years. The city council swiftly cleans these without further comment on the meaning of the monument. The graffiti in the photos says: “GET THIS SHIT OUT OF HERE”, “SHITY SETTLERS OUT”, “FASCISTS OUT”, and painted in red, “OPPRESSORS”. Photo: Câmara Municipal do Porto”

“Collection of graffiti on the monument in recent years. The city council swiftly cleans these without further comment on the meaning of the monument. The graffiti in the photos says: “GET THIS SHIT OUT OF HERE”, “SHITY SETTLERS OUT”, “FASCISTS OUT”, and painted in red, “OPPRESSORS”. Photo: Câmara Municipal do Porto”

“Extreme right-wing party Ergue-te (formerly PNR) celebrates the restauration of independence from Spain next to the MECP. Invitation for the 2019 festivities with the call “It is important to restore. Now!” Photo of the event with graffiti in the background. Photo: Partido Ergue-te”

“Extreme right-wing party Ergue-te (formerly PNR) celebrates the restauration of independence from Spain next to the MECP. Invitation for the 2019 festivities with the call “It is important to restore. Now!” Photo of the event with graffiti in the background. Photo: Partido Ergue-te”

“Porto city council swiftly cleans these inscriptions, reporting when it does on its website, but failing to contextualise its history or meaning today, instead appealing for “respect for the city’s patrimony, independently from any judgement made of the historical context in which political acts may have occurred.” The city council includes the monument in its tourist routes, again without explaining its history. In 2019, the monument became the focus for a gathering organised by an ultra-right-wing party to commemorate the Portuguese restauration of independence from Spain.”

Lisbon - Portuguese World Exhibition

“In 1940 (…) This new exhibition served to politically consolidate the regime, and with it an idealised version of Portuguese identity, responding to mounting international pressure concerning its colonial domains.”

“Around the Square of the Empire, the exhibition was organised in four sections: the historical section, including pavilions on Portuguese conquests, independence and discoveries; the regional centre, with Portuguese villages and pavilions; and the colonial section, offering an ethnographic journey through the overseas provinces. The colonial section had streets named after regions of the empire, like in Porto, and inhabitants of different countries of the empire living in simulated environments, however, in fewer numbers than in Porto.”

“The exhibition was visited by three million people, and filmed for posterity.”

"(...) as Peralta remarks, without historical scrutiny, thus allowing for a sanitised version of colonial history, in which the imperial was equated with the civilisational quality of Portuguese colonialism, mixing distinct temporal and geographic scales to form an idealised and mystical “Portuguese identity” associated with Portuguese maritime expansion and solitary heroes creating collective epic narratives."4

“In 1983, the Monastery of the Hieronymites and the Tower of Belém became UNESCO world heritage sites.”

"(...) As Peralta remarks, narratives that were previously mobilised because of ideological agendas are now repositioned in reference to the demands of the consumer and leisure markets and tourism, with the empire making place for the voyage, looking to build a story of these locations that can add revenue to the tourist industry."5

“In 1960, as Portuguese colonialism came under increased scrutiny, Estado Novo returned to the narrative of the discoveries to commemorate 500 years of the death of Henry the Navigator and the decision was made to re-erect the monument on a larger scale for this occasion.”

“Around the monument, the pavement—a gift from the South African apartheid regime—presents a mappa mundi and a compass rose.”

"Hyperbolic language is used to surround the monument with myths and stories of the sea, conveying ideas of permanence and strength, and positioning the Portuguese people as “uninterruptedly transmiting the sacred blood” of their heroes. In this way, binding bodies of the past to the present and future, in a rhetoric that still holds a strong grip over Portuguese society, which can be perceived in the difficulty in accepting other narratives that contest or disturb this account of history, and in revisiting the end of colonisation or its violence."

“Since then, it has become a favourite tourist destination, with most visitors remaining oblivious to the meaning of what they are experiencing, as city guides and tours focus on the narrative of discoveries, while visitors take superficial snapshots of the pavement, monument and river.”

“With its strong visual presence and imposing symbolism, the Monument to the Discoveries has been the subject of a number of activist and artistic interventions by contemporary artists, including Ângela Ferreira (Mozambique, 1958) and Kiluanji Kia Henda (Angola, 1979)."

“In denying the violence of Portuguese colonisation, manifold voices and perspectives remain invisible, opening public space to important questions about engaging with this legacy in a critical way.”

"The philosopher develops the idea of inscription in relation to this silencing, proposing that today the Portuguese still live in the shadow of this erasure and therefore in a state of non-inscription. Gil elaborates on the idea of re-inscription as a way of making visible what is omitted and opening up the affective to dissensus. I believe that as symbols these monuments can be explored in terms of their ability to re-inscribe affective registers that differ from official versions, opening up a public space for dissensus."6

“The movements of the past on the present can be seen as a form of haunting that remains invisible until discovered, or visible when represented.”

“In unsettling homogeneous views of history, linking the present to the past, and shaping the present towards the future, these monuments “haunt” not only by asserting a certain narrative over time, but also by continuously inscribing their materiality in the situatedness of the present, never claiming to tell a story in universal terms” (see Ghosts, Spectres, Revenants. Hauntology as a means to think and feel the future.)

“In talking about this monument, Ferreira believes in the possibility of reading buildings as political texts, proposing to not only tell a story as historian, but “to identify the buildings as metaphors, knowing how to articulate critical readings brought around them;"7

“In Descobertas/Padrão dos Descobrimentos (2007), Henda photographed a group of young people on top of one of the ramps of the monument, posing and leaning against its historical figures, dwarfed by their colossal scale.”

“After its creation in 2007, Henda’s work still draws scrutiny from the media: in 2017 when the photograph was part of an exhibition taking place inside the monument,) and more recently in the controversy around the photograph being bought by the city council, without knowledge of the artist, who had promised to donate part of its profits to the association that those in the photo belonged to (which happened later). The conversation became public and brought about a discussion about the work, its relation to the city and its symbolism, which demonstrates that in their circulation these works also create important moments for debate.”

“I have begun by creating silicone casts that become a concrete way of studying the monument in public space. The activity of creating the casts—with the necessary preparation and drying times—demand a period of being physically very close to the monument, extending a relation of observation to a prolonged experience that involves close witnessing and bodily encounters.”

Footnotes

-

Peralta, Elsa. “Fictions of a Creole Nation: (Re)Presenting Portugal’s Imperial Past”. In Negotiating identities: constructed selves and others. Edited by Helen Vella Bonavita. Amsterdam and New York, NY: Rodopi. 2011. p. 193. Quoted by B. Alves. ↩

-

These ideas paved the way to the later formulation of Portuguese exceptionalism in the notion of luso-tropicalism, proposed by Gilberto Freyre. See Anderson, Warwick, Roque, Ricardo and Santos Ricardo Ventura (eds.). Luso-Tropicalism and Its Discontents: The Making and Unmaking of Racial Exceptionalism. New York, NY, and Oxford: Berghahn Books. 2019. Quoted by B. Alves. ↩

-

Vicente, F. “’Rosita’ e o Império Como Objecto de Desejo”. Publico, Ípsilon. 25 August 2013. Available at https://www.buala.org/pt/corpo/rosita-e-o-imperio-como-objecto-de-desejo. Quoted by B. Alves. Commissioner of the exhibition, Augusto de Castro. Cited in Peralta, Elsa. ↩

-

Commissioner of the exhibition, Augusto de Castro. Cited in Peralta, Elsa. “A composição de um complexo de memória: O caso de Belém, Lisboa” In Cidade e império: dinâmicas coloniais e reconfigurações pós-coloniais. Edited by Nuno Domingos and Elsa Peralta. Lisbon: Edições 70. 2013. p. 380. ↩

-

Peralta, “A composição de um complexo de memória”, p. 389. ↩

-

See Gil, José. Salazar: A Retórica da Invisibilidade, Lisboa: Relógio d’Água. 1995; and Gil, José. Portugal, Hoje: O Medo de Existir, Lisbon: Relógio d’Água. 2007. ↑ ↩

-

Ferreira, Angela. “Os limites do poder do Padrão dos Descobrimentos e o retorno ao arquivo” In Retornar: Traços da Memória do Fim do Império. Edited by Elsa Peralta, Bruno Góis and Joana Oliveira, Lisbon: Edições 70. 2017. p. 351. ↩