How can experimental writing help deconstruct the celebrated narratives of colonialism that define Portuguese national identity?

Introduction

In Portugal, the violence of colonisation is not fully acknowledged but instead highly glorified. Every child undergoes a socialisation process that fosters a strong national identity aligned with the colonial period, called “Descobrimentos” (“Discoveries”). This is executed through a selective apparatus for the production and distribution of knowledge in schools, monuments, public spaces, language and other tools, as well as at home. The violence is always omitted, minimised or relativised, shapeshifting into the spread of christian faith, commercial trade towards globalisation, a glorification of “heroic” navigation deeds, or the “civilisation” of other cultures.

One of the mechanisms is the mandatory school reading of Os Lusíadas. This very famous book is an epic poem written by Camões in the 16th century, that recounts a fictive version of the first journey to India by sea. It contains 10 cantos, consisting of 8816 ten-syllable verses and 1102 eight-line stanzas. The rhymes are alternating and paired.

Here I investigate how I can rewrite Os Lusíadas, using experimental writing together with texts, books, media, scripts, and other artifacts of de-colonial authors with an emphasis on Lusophony. In this text, I create a solid understanding of why I am doing this, its context, meaning, relevance to this day, resources and methodologies of work. This is an unstable research, in constant change through time and collaboration..

First I explain how colonial violence has been whitewashed for the last decades and in which ways colonialism is still celebrated in today’s Portuguese society, with Os Lusíadas functioning as a beacon for national identity. Later I dive into its mythification through epic poems and present the methodologies for rewriting the original.

Celebrated narratives

Although the traffic of enslaved peoples was practiced in the African continent prior to Portuguese arrival, Portugal significantly boosted the practice through the creation of the Atlantic trade of enslaved people, transforming it into one of the most lucrative forms of international commodity at the time, and setting a racial order until today. Capturing was first conducted through direct raids on the the African coast, and later through organised stations whose supply was either a product of war prisoners, unjust judicial trials (analogous to contemporary US prison systems) or earlier social status.1 Later, the practice was replicated by other European nations, becoming “the largest forced human migration in history” affecting 10-15 million people.

Today, throughout the whole country, you can find traces of celebration of the colonial period, without looking very far. This goes from monuments, statues, objects, museums, street names and festivals, to its presence in music, what is or is not considered language, in education, or even simple interactions with others.

Monuments, streets and festivals

Having lived in the south of Portugal, up until 17 years old (2014), I was always confronted with the economic discrepancies between retired northern europeans and the locals. Whole cities, like Vilamoura or Vale de Lobo, were and are completely catered to this social class (called estrangeiros/foreigners, rather than immigrants), with lavish golf resorts, beach hotels, empty holiday mansions and whatnot, while the basic needs of the local population remain chronically under-resourced, e.g. public transport or healthcare. Beaches, dunes and biodiversity have also been destroyed for the sake of touristic profit.

Clearly there was an intentional effort and money put into making higher social classes in Algarve more comfortable, yet none into accommodating a much older class driven from the former colonies, even though this region was the birthplace of the colonial period (specifically in Lagos). In those 17 years I never saw or heard anything regarding this.

In 2016, the city opened the Núcleo Museológico Rota da Escravatura, the only museum about slavery in the country, located in plaza Infante D. Henrique (the perpetrator of the first navigations) with a statue of his in the middle. If you walk around, you find some more symbols, such as Vasco da Gama and Camões, as well as a statue of Gil Eanes, who “first” passed through Western Sahara, where the first Africans were kidnapped and subsequently shipped to Portugal2. While visiting you learn that during excavations in 2009 for a parking lot, they found around 155 bodies from enslaved people that had been dropped in a rubbish dump3. The main street of the city is called Avenida dos “Descobrimentos”. Every 2 years the city holds a festival4 cosplaying the colonial epoch and celebrating the local “heroes” for their “great adventure”, “challenging” the unknown and “transforming” the ocean into a “bridge” between two continents.

The use of language and assertion of pride in the city, such as claiming ”(…) desvendaram os primeiros segredos dos oceanos (…)” 5 (uncovered the first secrets of the ocean), the placement and connection between monuments, obsession with glorifying this period, displaying desecrated bodies in the museum6 and building a mini-golf court on the burial site7, while omitting references to the violence, kidnapping, enslavement and murder of displaced peoples8 leaves the slavery museum looking like a clear performance of a fake reconciliation with the past. Moreover, the president of the municipality at the time referred to the museum as a driver for tourism.9

Lisbon does not fall much further. In 2017, the association DJES (Association of Afrodescendents) proposed to the city’s council the construction of a memorial site paying homage to the victims of the Atlantic trade of enslaved people. The municipality agreed, and DJES made an open-call for 5 invited artists to foresee the project. The idea of Kiluanji Kia Henda - a plantation of sugar cane - was chosen, but after 8 years is yet to become a reality, as the city keeps creating various obstacles towards execution, including inexplicable waiting times between replies, changing previously set locations, producing fake images in relation to the artist’s original idea, etc. A similar case happened with Batoto Yetu Portugal, who created 20 signs and a bust honouring African presence in Lisbon. The artworks were fully completed in 2020, there was a budget for setting them up in the city funded by the association itself, yet the process remained hanging until 2024.10 One could argue in defense for the economic condition of the country, however the year before the government spent 75 million euros11 to receive the pope, due to its high touristic turnover.

Throughout the city you can find numerous instruments glorifying the colonial period, such as Padrão dos “Descobrimentos”12(including Camões writing Os Lusíadas - ^fig-padrao), countless caravels and compasses drawn in the sidewalks (^fig-rosa-dos-ventos, ^fig-rosa-dos-ventos-lagos, ^fig-caravel-lisboa), statues of the many colonial participants (like Father António Vieira13 surrounded by indigenous children, erected in 2017 - ^fig-padre), shopping malls alluding to the colonial period (e.g. Vasco da Gama, Colombo), as well as other infrastructures, like Rua do Poço dos Negros, that appears to be one more pit for the dead bodies of the enslaved.14

Fig. 1 - Padrão dos “Descobrimentos” saying “Blindly sailing for money, humanity is drowning”. Publico, https://imagens.publico.pt/imagens.aspx/1611845?tp=UH&db=IMAGENS&type=JPG

Fig. 1 - Padrão dos “Descobrimentos” saying “Blindly sailing for money, humanity is drowning”. Publico, https://imagens.publico.pt/imagens.aspx/1611845?tp=UH&db=IMAGENS&type=JPG

Fig. 2 - Rosa dos Ventos gifted by the South African Apartheid regime. Portuguese Museum, https://portuguesemuseum.org/?page_id=1808&category=4&exhibit=&event=82#images-1

Fig. 2 - Rosa dos Ventos gifted by the South African Apartheid regime. Portuguese Museum, https://portuguesemuseum.org/?page_id=1808&category=4&exhibit=&event=82#images-1

Fig. 3 - Rosa dos Ventos at Lagos

Fig. 3 - Rosa dos Ventos at Lagos

Fig. 4 - Caravel sidewalk in Lisbon. Bucket List Portugal, https://bucketlistportugal.com/calcada-portuguesa-the-art-of-portuguese-pavement/

Fig. 4 - Caravel sidewalk in Lisbon. Bucket List Portugal, https://bucketlistportugal.com/calcada-portuguesa-the-art-of-portuguese-pavement/

Fig. 5 - Statue of Father António Vieira in Lisbon. A.MUSE.ARTE, https://amusearte.hypotheses.org/files/2020/06/antoniovieira.jpg

Fig. 5 - Statue of Father António Vieira in Lisbon. A.MUSE.ARTE, https://amusearte.hypotheses.org/files/2020/06/antoniovieira.jpg

Similarly in Porto, you can find ruins of the colonial period15 without any affirmations surrounding its inherent violence. The city not only has an interactive museum catered to children - the World of Discoveries16 -, but also held the “Portuguese Colonial Exhibition” in 1934, similarly to other European countries.

Exhibitionist governments

The exhibition took place in Palácio de Cristal, where 1.3 million visitors could go by foot, train or cable car, visit a theatre, a zoo, a tea house, monuments, as well as inhabitants of the former colonies living on display for the duration of the event, simulating their “real” habitat. By the entrance stood a temporary statue - the Portuguese Monument to Colonial Effort -, which was later replicated in stone, dismantled in 1943, and re-erected in 1984 under the city’s orders. The statue has been contested through grafitti and art exhibitions (e.g. Unearthing memories, ^fig-fascists-out), but also celebrated by an extreme right-wing party.17

Fig. 6 - Photo of Portuguese Monument to Colonial Effort saying “FASCISTS OUT”. Câmara Municipal do Porto, https://parsejournal.com/article/turned-into-stone-the-portuguese-colonial-exhibitions-today/

In Lisbon, a similar exhibition was held in 1940 - the Portuguese World Exhibition -, attended by 3 million visitors, that left behind the Padrão dos “Descobrimentos” mentioned earlier. Both exhibitions, as Alves notes (together with Peralta and Vicente), contributed to the stereotype of the colonised as uncivilised by presenting them as “primitive” in “their natural habitats”. Vicente speculates that these spaces served to eroticise the empire, making a parallel between femininity (becoming colonised) and the imperial European masculinity that would dominate it.18

A more subtle example was Expo 98, commemorating 500 years since Vasco da Gama arrived to India. Dressing the ocean as the main theme - “The Oceans, a Heritage for the Future” - and associating it with greenwashed environmental protection, the expo attempted to rearrange Portuguese earlier national identity (centred around imperialism and othering) to meet the symbolic demands of the new European democracies’ neoliberal agendas. Commodifying the past into “an exchange value in the cultural and tourist consumption market” and showcasing an open, expansionist and enterprising attitude to secure foreign investment.19

All these exhibitions helped sanitise colonialism, establishing a mystical national identity originating from “the Portuguese as a marine folk, descendant of the ‘heroic discoverers of the world’, held by fate to the higher call of helping others ‘reach civilisation’”, “uninterruptedly transmitting the sacred blood” of their heroes, while perpetrating collective epic narratives. 20 Lusotropicalism, as an ideological tool, further helped legitimise the myth, stating that Portuguese colonialism was (in comparison to other colonisers) softer, peaceful, gentle, hybrid, miscegenated, multicultural, and somehow Creole21, completely omitting all the sexual violence.

Gilberto Freyre, the developer of this theory, was invited by the government in the 1950s, to visit and analyse the former colonies. His “independent” views on the benign nature of our colonialism became the official doctrine of the dictatorial regime, in order to appease the criticism from other European nations whose colonial regimes had collapsed. Disseminated through media, books or official documents, the ideas became ingrained in Portuguese culture22, echoing in the words of our current President, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa (whose father, interestingly enough, used to be a Governor-General of Mozambique between 1968-197023 ).

Language and things

In 2016, our President claims that we, as a nation, have an exceptional ability to learn and include others, creating bridges between cultures, civilisations and continents. In 2017, in a visit to Senegal, he recognises slavery’s injustice and consequently affirms that our country abolished it in 1761 (a lie pushed as anti-racist discourse24). Protests arose calling for the President to apologise for Portugal’s role in slavery, which he still hasn’t. In 2018, in Boston, he states that the USA is a big country, but that Portugal is even bigger, the biggest country in the world. In 2019, in the Day of Portugal (the day of Camões’s death), Marcelo again insists that we are a nation at ease with its past, actively constructing the present and arming the future, encompassed by many ‘Portugals’ that extend beyond its geographic boundaries. This rhetoric could be comparable to 1934’s propaganda,^figpequeno.25

Fig. 7 - Map from 1934’s Colonial Exhibition, saying “Portugal is not a small country”. Al Jazeera, Courtesy of Paulo Moreira. https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/PORTUGAL_NAO_E_UM_PAIS_PEQUENO.jpg?resize=770%2C513&quality=80

Fig. 7 - Map from 1934’s Colonial Exhibition, saying “Portugal is not a small country”. Al Jazeera, Courtesy of Paulo Moreira. https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/PORTUGAL_NAO_E_UM_PAIS_PEQUENO.jpg?resize=770%2C513&quality=80

In the same year in WebSummit, Lisbon’s mayor offered an astrolabe to the founder of the conference, pointing out that “Lisbon was the capital of the world five centuries ago, (…) From Lisbon departed a great adventure that connected the human race. Today it is you, the engineers, the entrepreneurs, the creators, the innovators, the start-ups, all the companies”.26

The list goes on. Like I had mentioned before, you don’t have to look far; even the stamps I got at the post office were illustrated accordingly (^fig-stamps). The narrative bleeds throughout dialogues. Paradoxically, a great amount of words from former colonies’ enter our quotidian, e.g. bué and bazar (from Kimbundu mbuwe and kubaza, respectively), yet these are not considered languages by the Portuguese standard (e.g. Badiu) and words are demoted to slang. As if the miscegenation between languages is only desirable when the objective is to re-iterate our inclusive nature for later commodification.

Fig. 8 - Stamps from the post collected in 2023, saying “5 centuries of Portuguese presence in the Southern Seas”.

Fig. 8 - Stamps from the post collected in 2023, saying “5 centuries of Portuguese presence in the Southern Seas”.

Os Lusíadas and education

This leads me to Os Lusíadas. This is THE book - unmatched, unrivaled, irreplaceable, incomparable, transcendent, the pinnacle of poetry in the eyes of Portuguese society. Second to this would only be A Mensagem, its homage whose objective was to awaken Portugal’s “greatness”. In the latter, Fernando Pessoa sought to rebuild national identity through myth and memory, revisiting Portugal’s past prophetically, contrasting it with the 20th century’s decline. Like Camões, he glorifies national “heroes” and urges for a cultural revival into the “Fifth Empire”27.

In school, it’s mandatory to “analyse” both Os Lusíadas and A Mensagem. Yet the efforts to reflect upon the underlying issue behind these two texts are minimal. In 8th grade History books, while there is a slight connection between the “discoveries” and violence (predominantly on side notes), there is no mention of our founding contribution to the Atlantic trade of enslaved people, for how long and how it occurred, how many people were displaced or died at sea, or its overall impact in the present day. Mostly you learn about the chronology of occupation and economics that converge in “Portugal was the main economic European power in the second half of XVI”.28 Once we move into 9th grade Portuguese studies, Os Lusíadas is taught under the framework of narrative text, epic poetry, pronouns, rhymes, metaphors, periphrases, i.e. “objectively”, without any mention of colonisation.29 The connection between the two is lacking.

For example, near the end of canto I, the Portuguese arrive to Mozambique’s islands and come across the moors, who themselves (through the imagination of Camões) describe the locals as “sem Lei e sem Razão” (without Law or Reason). This immediately reveals and justifies the ‘civilising’ mission. The moors, guided by Bachus who is preventing the “inevitable” Portuguese “fate” of arriving to India, attack us, even though we had been “very generous”. We win the battle and turn out to be the victim of this unprovoked violence - a projection of the oppressor onto the oppressed.30

No mar tanta tormenta e tanto dano, Tantas vezes a morte apercebida! Na terra tanta guerra, tanto engano, Tanta necessidade avorrecida! Onde pode acolher-se um fraco humano, Onde terá segura a curta vida, Que não se arme e se indigne o Céu sereno Contra um bicho da terra tão pequeno?

By sea what treach’rous calms, what rushing storms,

And death attendant in a thousand forms!

By land what strife, what plots of secret guile,

How many a wound from many a treach’rous smile!

Oh where shall man escape his num’rous foes,

And rest his weary head in safe repose!31

Myths and epics

The traces of colonialism in other European countries, as well as current neocolonialist policies, are numerous. For example the 2024’s unrest in New Caledonia, or Macron’s recent statements regarding Burkina Faso.32 Yet, they feel different to contemporary Portuguese efforts. For an empire who claims to have been so powerful, becoming one of EU’s poorest countries certainly makes it look more like a myth.

My father’s childhood was marked by poverty and watching dead bodies come back from the colonial war during Salazar’s dictatorship. My mother’s by an absent father, smuggled to Paris to work in construction, avoiding military duties. The 14 years of war drained the country by 1974 consuming around 40% of the national budget.33 But even before that, Portugal was a declining empire, and Os Lusíadas personifies this through the ominous figure of Velho do Restelo, emerging as a critic of the ambition and greed that drove the colonial expansion. Indeed, mere years after the book was published, the king dies in Alcácer-Quibir, plunging the country into Spanish ruling and intensifying Portuguese-Dutch conflicts (due to the 80-years war with Spain). The Dutch disrupted the Portuguese colonial network, capturing Indonesian territories, Mallaca, São Tomé, the north of Brazil, Luanda, etc.

After restoring independence and left with a shrunk empire, Portugal turned to Brazil’s gold reserves. In 1750, Portugal’s output per capita was considerably higher than France or Spain’s. A century later, it became Western Europe’s poorest country. Brazilian gold influx enriched the country’s elites, causing a 30% real exchange rate appreciation, making labour and capital shift to luxury goods and services, and consequentially collapsing domestic industries and leaving the country de-industrialised, “reduced to a poor, quasi-dependent primary product exporter in Britain’s orbit” - a phenomenon known as Dutch disease.34 Fast-forwarding abruptly, Napoleonic wars led the king to flee to Brazil and claim its independence. The dissolution of the former colony left Portugal economically peripheral, with no industry, faced by a crippling British ultimatum and consequent civil war. This paved the way to the first republic, which equally unstable, culminated in Salazar’s dictatorship from 1930 till 1974.

During that period, Portugal was willing to go beyond economic exchange value - it gripped on to the territories even when they weren’t profitable. It saw them as a symbol of its “heroic” past, retaining them “no matter how small or poor”, “fearing that any reduction would weaken Portugal’s claim to be a world ‘civilizing’ power”.35 Following “decolonization”36, a dominant memory emerged as an adapted colonial myth legitimising the transition as a mutual, fraternal liberation retaining strong cultural bonds. It depicted Portugal as a soft coloniser, multiracial and naturally capable of managing future post-colonial relations. This perspective not only guided Portuguese foreign policy to fit an identity that could prove advantageous when integrating EEC/EU37, but also undermined the liberation movements inspired by Amílcar Cabral, that restored Portugal’s democracy. The Armed Forces Movement that staged the coup d’état on April 25, 1974, were born in Bissau in August 1973 “led by war-fatigued junior officers who admired Cabral”. His party, the PAIGC was also in contact with Mozambique’s FRELIMO and Angola’s MPLA.38

The empire has been in free fall since the epic poem was written. The country still lives an inferiority complex, struggling to accept its subaltern position in Europe. Lacking an identity other than coloniality; mythifying oneself through the remnants of this “glorious” empire, to compensate for a longing to be what it “once was”; and avoiding the “painful necessity of confronting” its smallness. You see it in Salazar’s words: “this union with the overseas territories gives us an optimism and sense of greatness that are indispensable in energising us and driving away any feelings of inferiority.”39 You see it in Marcelo’s words above. You see it in Saudosismo - a literary movement whose basis is the feeling of saudade (longing for). You see it in Os Lusíadas, where the fictively retold journey establishes a fundamental pillar of Portuguese culture.40

The book could have been a novel or lyrical poetry, but the author deliberately chose epic poetry, a tool close to that of myth. He himself states it by asking Virgil’s Aeneid and Homer’s Odyssey to be ceased immediately in canto I.41 In Hegel’s Eurocentric perspectives42, this kind of poetry is not an expression of personal feelings or individual reflections, it’s the manifestation of a national spirit presented through a “heroic” event rooted in a nation’s collective consciousness; integrating a “total view” (divine, natural and human) and balancing individual agency with a divine mandate.43 In our case, “expand christian faith” and “civilize the world”, consolidated by multiple papal bulls (e.g. Dum Diversas, that authorised Portugal to extract resources and subjugate Africans to “perpetual servitude”). The event was the journey to India that was semi-orchestrated by Venus and Bacchus interventions expressed through natural phenomena, like tempests or favourable currents, i.e. colonial expansion framed as a cosmic battle. However, in Hegel’s view, one could say that Os Lusíadas is not actually a pure epic for its self-conscious nationalism and didactic interventions, but instead, as Lourenço puts it - a coherent war machine44 - geared towards inspiring a falling empire.

To justify land and body theft, filiation becomes crucial and takes place through Christianity’s mechanisms as a linear and universalising spirit. In other words, anything that was opaque to these believes, anything that was not affiliated (not from the same root), the other, had to be either assimilated or annihilated, as it posed a threat to it’s universal truth.45 A threat analogous to how Palestine has been framed by Israel - an opaque obstacle to a mythic filiation rooted in religious narratives. The concept of filiation is visible, for example, in stanza 53 of Canto I.

“Somos (um dos das Ilhas lhe tornou) Estrangeiros na terra, Lei e nação; Que os próprios são aqueles que criou A Natura, sem Lei e sem Razão. Nós temos a Lei certa que ensinou O claro descendente de Abraão, (…)”

“Rude are the natives here,” the Moor replied;

Dark are their minds, and brute-desire their guide:

But we, of alien blood, and strangers here,

Nor hold their customs nor their laws revere.

From Abram’s race our holy prophet sprung, (…)”31

The heirless king’s death in 1578, started a century-long pursuit of legitimation through myth-making - bypassing bloodlines, and transforming into a lineage of “heroes” held together by “inevitable fate”. Rather than confronting the end of this fictive filiation and recognise it as a violent imposition, “decolonisation” was refashioned to fit a new national identity - not a loss of legitimacy but a continuation of Portugal’s role, not as an imperial patriarchy, but as a benevolent mediator between Europe and the Global South. It revealed not the collapse of the myth, but its plasticity till today.

Methodologies

Filiation, like a root, means the absolute exclusion of the other. Unlike a rhizome, where new shoots can emerge and become their own individuals, spread but kept connected through a decentralised network.46 In Glissant’s Poetics of Relation (the book that has been serving as the foundation for my work), an example of a rhizome would be the formation of creolised societies and the creole languages themselves. The forced displacement of Africans taken from multiple origins, carrying an opaqueness to each other and to the unknown land without their roots, formed complex and often untraceable new identities, languages, and culture through the Relation with the Other (opposite to a singular dominant root embodied by the colonisers).47 I would like to embody this idea of rhizome through experimental writing.

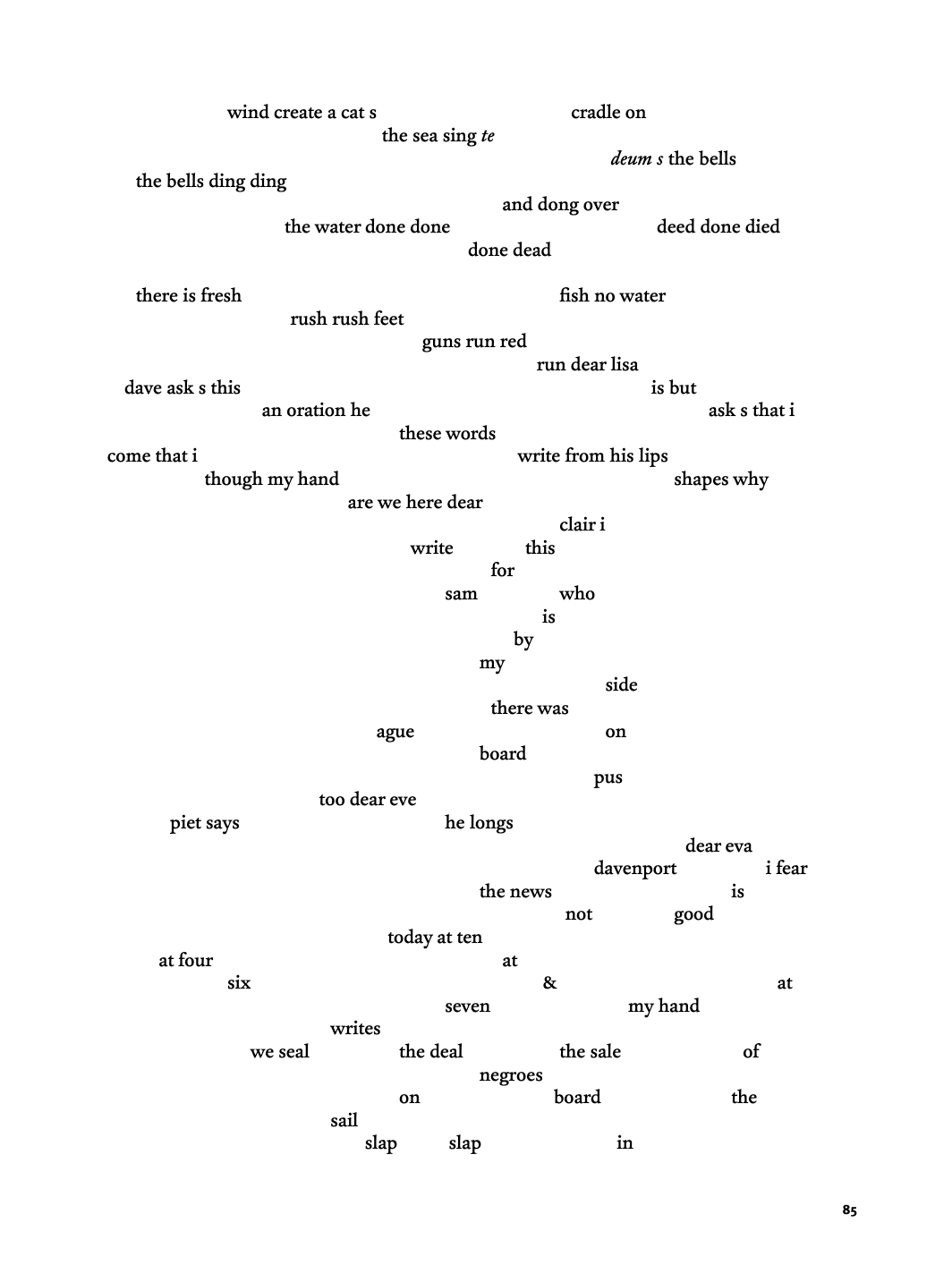

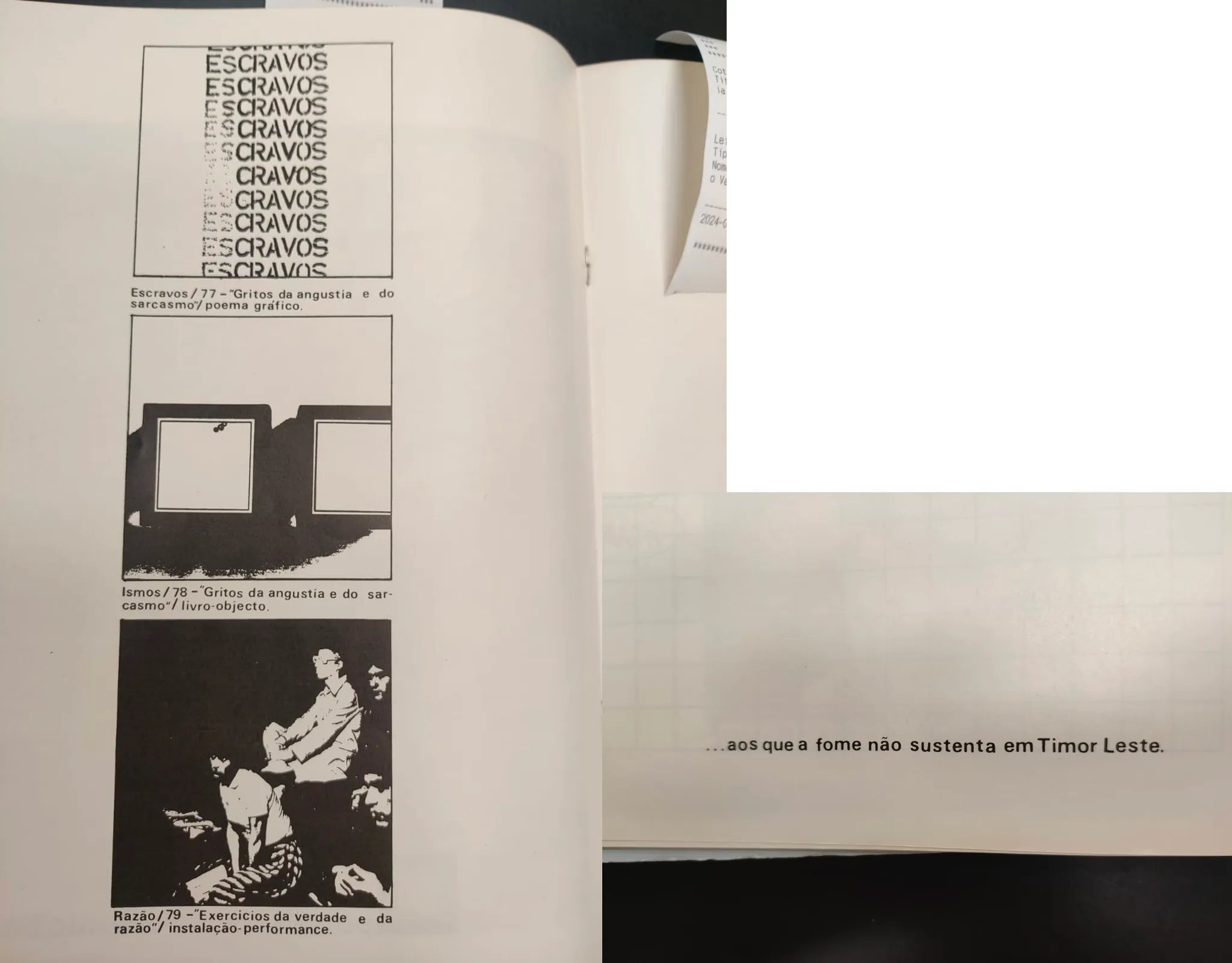

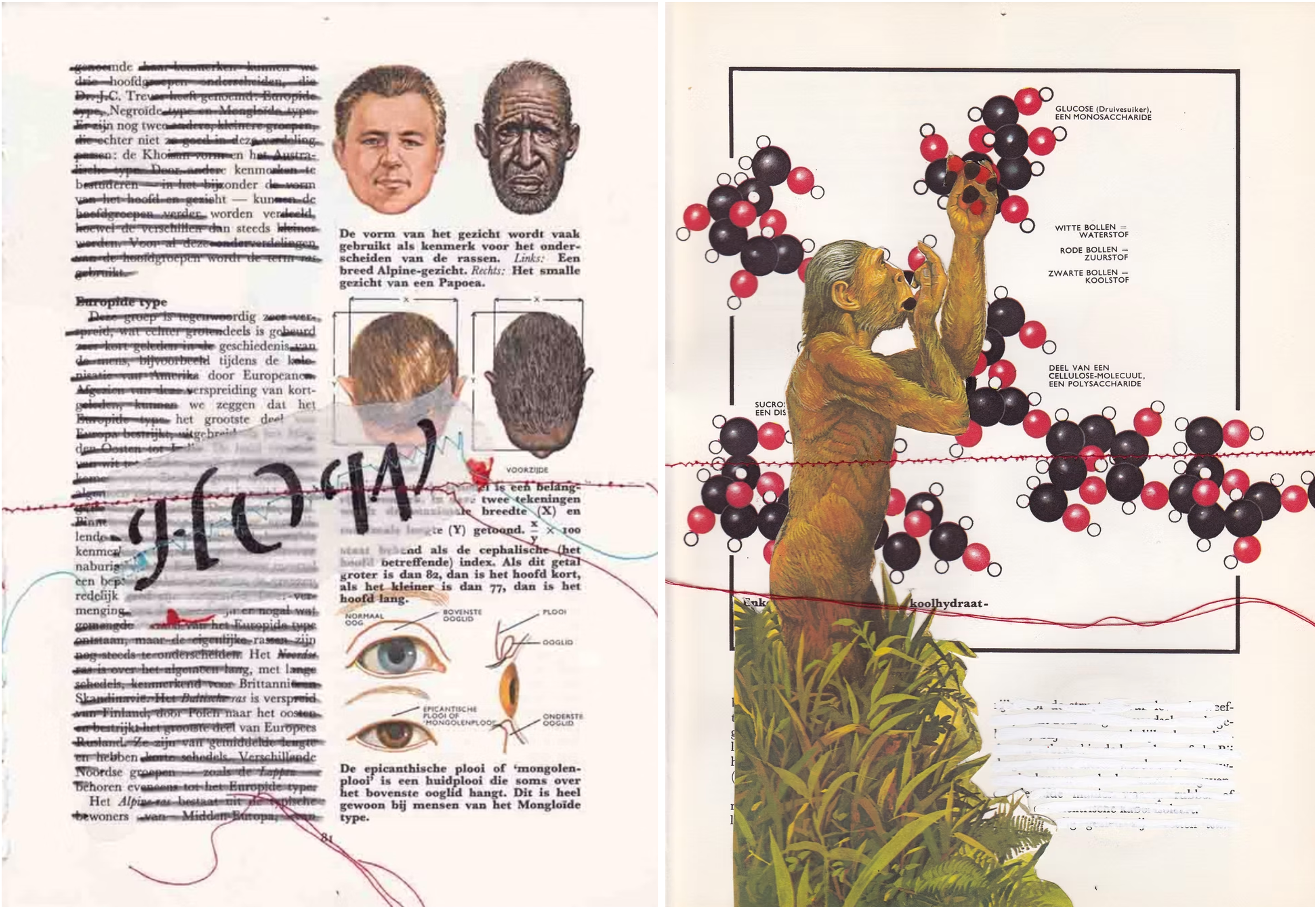

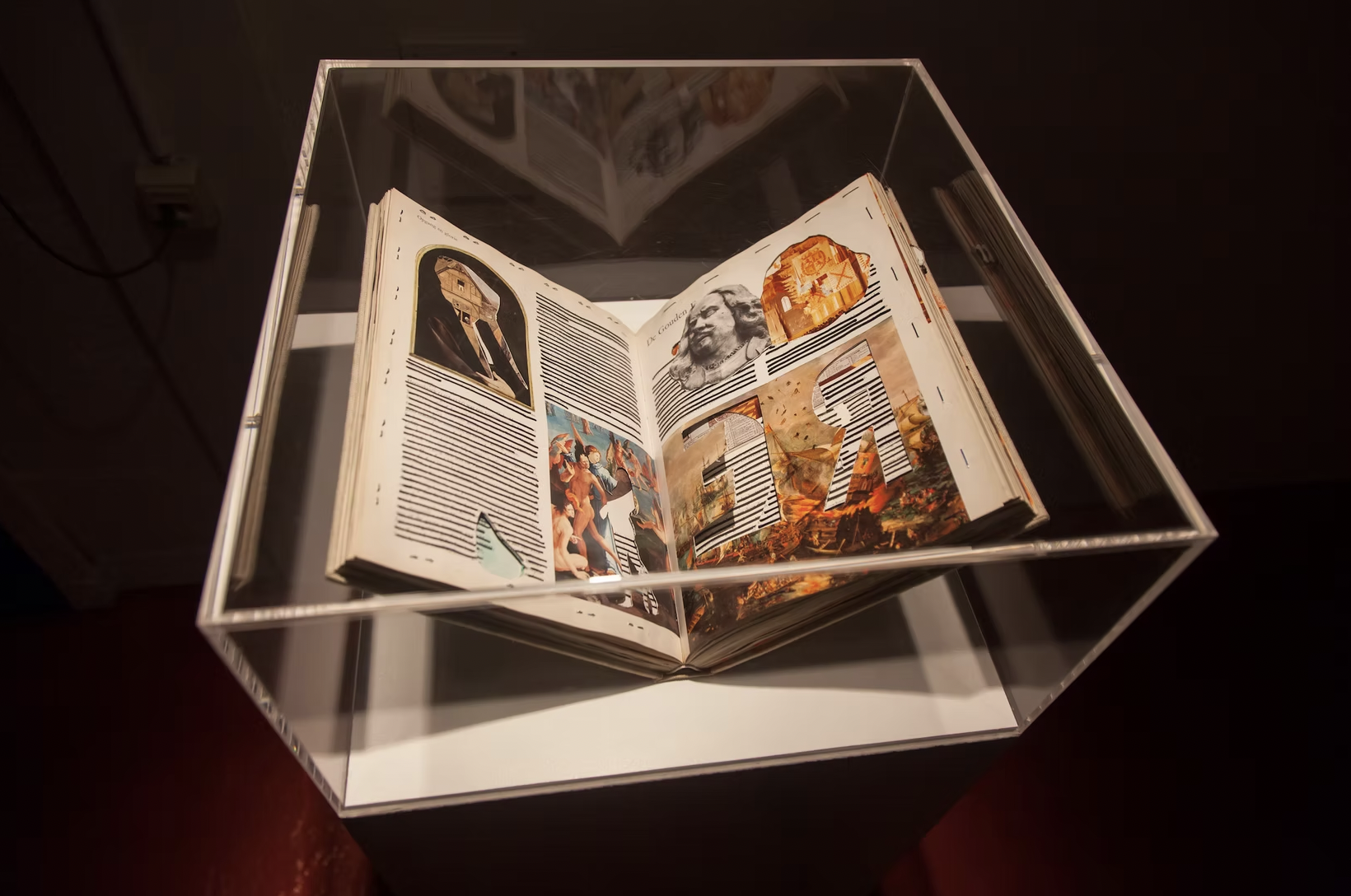

Experimental writing is difficult to define. To grasp the term, I have a small library of references, ideas and techniques that helps in understanding the many shapes it can take: “cut a page in half and switch sides”, “write without the letter A”, “blackout text”, “cut syllables, sentences, paragraphs or shapes, reorder them”, “make footnotes that comment on missing text”.48 For example, NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! erases parts of the legal documents of Gregson v. Gilbert, a case about 150 Africans who were thrown overboard by the captain of a enslaved ship (^fig-zong). In Portugal, within the 1960’s experimental poetry movement (PO.EX), Barros’s Gritos de Angústia, transforms the words “escravos” (“slaves”) and “cravos” (carnations - the symbol of the 1974’s revolution) back and fourth (^fig-barros). In the Netherlands, Kaersenhout uses old history books as a medium for cut-outs, collages and texts (^fig-patricia).

Fig. 9 - Page 85 of Zong! by NourbeSe Philip.

Fig. 9 - Page 85 of Zong! by NourbeSe Philip.

Fig. 10 - Images from the book “Exposição de Poesia Experimental Portuguesa”. PO.EX.80. Galeria Nacional de Arte Moderna - Belém. Consulted in May 2024.

Fig. 10 - Images from the book “Exposição de Poesia Experimental Portuguesa”. PO.EX.80. Galeria Nacional de Arte Moderna - Belém. Consulted in May 2024.

Fig. 11 - Photos of the work “THE DREAM OF A THOUSAND SHIPWRECKS” and “We refuse…” by Patricia Kaersenhout. De Appel, Amsterdam. 2018. Photo: Konstantin Guz. https://www.pkaersenhout.com/copy-of-les-eclaireurs

Fig. 11 - Photos of the work “THE DREAM OF A THOUSAND SHIPWRECKS” and “We refuse…” by Patricia Kaersenhout. De Appel, Amsterdam. 2018. Photo: Konstantin Guz. https://www.pkaersenhout.com/copy-of-les-eclaireurs

Analysing Zong! through Glissant’s lens, the scattering of its words and phrases (and the intentional spacing they each have to breathe) refuses a hierarchical structure. Each fragment has its roots, but as whole, they become unpredictable and open-ended. The work is opaque as the text does not form a linear narrative, nor structures cohesive sentences whose meaning can be objectively extracted, or reduced in its complexity - it rejects logic in favor of an emotional resonance. In the helm of epic poems, St Lucian Derek Walcott’s Omeros “draws on the language, imagery, and themes of Homer, as well as Virgil’s Aeneid” to describe his struggle with mixed identity. This epic doesn’t follow a linear path and has no main protagonist, as the narrative jumps in time, between characters and his own voice.49

Rewriting Os Lusíadas

My point in rewriting the epic poem is not to criticise Camões. But rather to re-instrumentalize the symbolism and grandiosity that has been placed upon his book from the last centuries until now, and express the violent nature of our past. While there is numerous work tackling this very urgent concern,

- from academic texts (e.g. from Elsa Peralta, Ana Balona de Oliveira, Aurora Almada e Santos, Joacine Katar Moreira),

- to books (e.g. Memórias da plantação, Volta para tua terra, Toward final victory!),

- to music (e.g. Dino d’ Santiago, Azagaia, Povo pequenino - Fado Bicha),

- to films (by Welket Bungué, A Guerra, Quilombo, Sambizanga),

- to performances (e.g. by Panaibra Gabriel Canda, Opera to a Black Venus, De-Re-Memorization of Portuguese Colonialism and Dictatorship),

- to visual art (e.g. by Sandim Mendes, Mónica de Miranda, Irineu Destourelles, The singularity of Tchiloli - René Tavares, (Re)descobertas - Olavo Amado),

- to exhibitions (e.g. Unearthing memories, Problemas do Primitivismo – a partir de Portugal)

- and other artifacts or spaces (e.g. Jornal O negro, Hangar, Bazofo & Dentu Zona),

I am convinced that I can make a meaningful contribution by rewriting this treasured book through the words, sentences and paragraphs of these creators. More specifically, orchestrating cut-outs of the epic poem together with cut-outs from texts of de-colonial authors with an emphasis on Lusophony. The texts can be interviews, academic papers, songs, poetry, books, theatre pieces, performances, visual art, conversations, or others, all on equal grounds. To make use of a certain text, I engaged with it theoretically, the words are not just removed and decontextualised, since the point is not to assimilate or annihilate them, but to elevate them. Sentences are prioritised over words, in order to limit the amount of freedom I have with the emerging combination of texts. The more of the cut-out text remains, the more opacity is preserved.

Maintaining structure

The immediate question that arises is if it makes sense to keep the same structure as the epic poem. Although, Os Lusíadas is not completely linear (jumping back and fourth in time), it is chronological. Beyond that, it has delineated cantos, 1102 rigid stanzas and heroic-decasyllabic verses. Replicating this structure could mean to be rooted in the original. And while that is true, I can see advantages that lead me into taking that decision. Other than the divine elements and the nationalist rhetoric that praises the Portuguese, the structure of the epic is what makes it so mystical - creating such a work is perceived as extremely complex and genius. Choosing not to do so could mean losing an opportunity to overshadow its ingenuity - relevant when the goal is to dismantle it and actually talk about the underlying violence. Thus, it makes sense to create 1102 ABABABCC stanzas with decasyllabic verses, but in a non-linear narrative.

While making I realised that the decasyllables are counted as poetic syllables, rather than grammatical. For instance, te-le-vi-são (te-le-vi-sion) has 4 grammatical syllables, but 3 poetic syllables tle-vi-são (tle-vi-sion) in certain accents (e.g. in Brazilian-Portuguese it’s 4). Thus, in its structural-analysis there is an implicit accent preference. One could say that in the atrocities that led to creolisation, the original poem ironically lost its magnificent rigidity.

Collaboration

A crucial point for the work is how to incorporate multiple voices while operating from a Portuguese perspective and ensuring that multiplicity leads the reimagining, instead of a single authoritative voice. Collaboration is paramount in achieving this. I have been in conversation with Sandim Mendes, Tavares Cebola and Mariana Aboim, who have generously helped me navigate the project and its pitfalls. Tavares, a Mozambican researcher, provided insights on Mozambique’s politics, text and performance references as well as his own articles. With Sandim, a Cape Verdean artist from Rotterdam, I had the chance to discuss her opinion on the project, parallels between our works, references and fears. This conversation made me more certain about having co-authors write certain stanzas of the book with their own words. However, what exactly to request of them (in terms of structure) or how to navigate between intentional fragmentation and accidental incoherence, is still uncertain to me and highly depends on the availability of funding to pay for their work.

Another question is if and how to include other languages - if it makes sense to, for instance, use cut-outs written in Badiu, Macanese Patuá, Forro, Kikongo, Kimbundu, etc, when I don’t speak them. While incorporating these could prove useful at undermining the Portuguese language as a colonial tool, preserving opacity, refusing uniformity or a passive consumption of text, as well as fully capturing experiences that Portuguese can’t, I believe it should only be done in collaboration to prevent extractive linguistic tourism.

Typographies and Topographies

I see the outcome of the rewriting not just as a book, but as a library of resources that don’t currently belong to the mainstream bookshelves, or to the Portuguese literary canon. I think that the idea of making a new epic poem to characterise Portuguese society can drive enough curiosity in the public, and thus be able to achieve its role as gateway to other artifacts. For this reason, for a question of ethicality, and from an organisational standpoint while working, its imperative that the cut-outs used are clearly referenced. I have defined a specific font size and typography to each source (that may later become a design principle for the book), in order to map them (^fig-sources).

Fig. 12 - Photo of used sources in different font sizes and typographies

Fig. 12 - Photo of used sources in different font sizes and typographies

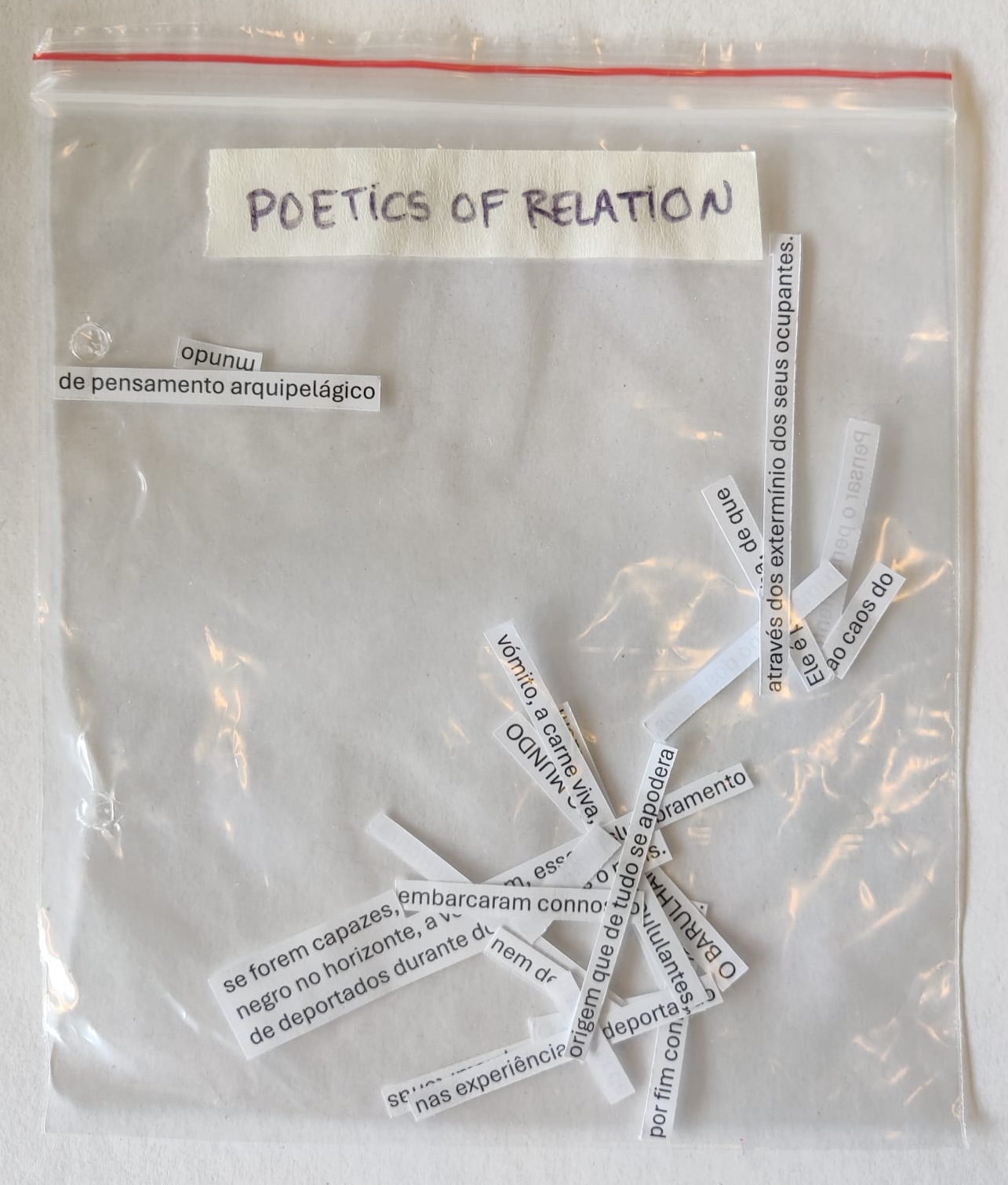

Each source has a bucket and a plastic bag for storage of cut-outs. What I choose or not to cut-out from a text is initially based on intuition and later on, as it becomes more complicated, on what can be puzzled into a heroic-decasyllabic-8-versed-stanza and the message I want to convey (^fig-org).

.jpeg)

Fig. 13, 14 - Photos of used sources organised

Fig. 13, 14 - Photos of used sources organised

On the parallelism with Os Lusíadas, I am still unsure on how to procede in terms of cantos, or if and how to relate each canto to the texts I am sourcing. I have been dissecting what each stanza means and which relations I can find, but also just cutting from the first canto and see what it can organically bring (see ^fig-diss).

.jpeg) Fig. 15 - Photo dissecting Os Lusíadas

Fig. 15 - Photo dissecting Os Lusíadas

Navigating chaos

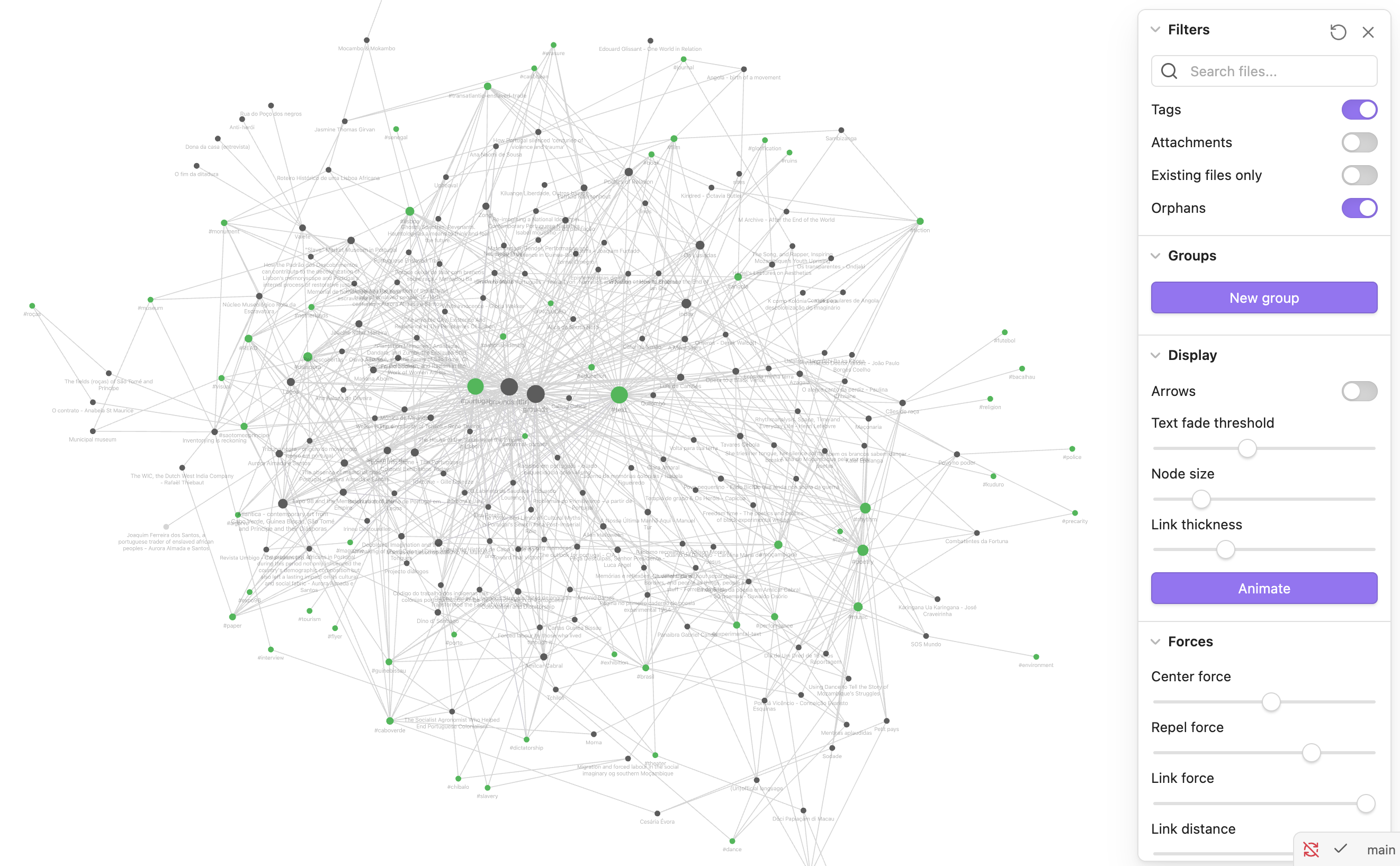

Due to the large amount of sources, I have decided to use the software Obsidian hosted online in this platform. Each page under the artifacts folder shall have its bibliographic reference, notes and a collection of tags (e.g. moçambique, performance, fiction), which allows for connections to later be found. Instead of hierarchically, I can visualise, navigate and search these sources through a graph view (see ^fig-graph).

Fig. 16 - Screenshot of the graph view locally.

Fig. 16 - Screenshot of the graph view locally.

End note

Os Lusíadas is a ruin of the past that has served and continues to serve as a means to create a violent world. In its rewriting there is the possibility to betray its legacy, to reinvent it and its role in Portuguese culture, to leave behind a different narrative for the future50 that can work as a tool to return “colonial pain and trauma to its thinkers”51. I see this project as a fertile ruin, an open incubator or a library - where new relations may be crafted from the collection of references that very literally compose the body of emerging text via this experimental writing approach.

Footnotes

-

Caldeira, Arlindo and João Almeida. Quinta Essência | Ep. 33. Tráfico de Escravos - Parte 1. 2023. https://www.rtp.pt/play/p319/e670327/quixnta-essencia and Almada e Santos, Aurora. Portugal and the invention of the Atlantic trade of enslaved people, 15-16th centuries. Project MANIFEST. 2023. https://www.projectmanifest.eu/portugal-and-the-invention-of-the-atlantic-trade-of-enslaved-people-15-16th-centuries/. ↩

-

Caldeira, Arlindo. The Portuguese “Slave” Trade. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, edited by Thomas Spear. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.903. ↩

-

Núcleo Museológico Rota da Escravatura, Museu de Lisboa. Text on A lixeira do vale da gafaria, observed January, 2025. Lagos. Photograph of text available at ^found-enslaved-bodies. ↩

-

Festival dos “Descobrimentos.” Lagos. Accessed May 7, 2025. https://festivaldosdescobrimentos.pt/www/. Quotes available at ^festival-colonial. ↩

-

Turismo do Algarve. Algarve. Lagos, Portugal: Turismo do Algarve, 2011. Photograph available at Brochura do Turismo de Portugal em Lagos. ↩

-

The Contested Histories Initiative. Slave Market Museum in Portugal. Contested Histories Case Study #130, June 2022. https://contestedhistories.org/wp-content/uploads/Portugal-Slave-Market-Museum-in-Lagos.pdf. Quotes available at ^displayed-body. ↩

-

Museu Digital Afro Português. O Cemitério de Escravos de Lagos. Lagos. Accessed May 7, 2025. https://museudigitalafroportugues.wordpress.com/sobre/reino-do-algarve/o-cemiterio-de-escravos-de-lagos/. Quotes and photograph available at ^burial-site. ↩

-

Moreira, Joacine, César Cardoso, and Mónica de Miranda, eds. TO DECOLONISE IS TO D.E.P.R.O.G.R.A.M.M.E. Systemic racism, body, gender and diaspora in arts. Atlantica: Contemporary Art from Cabo Verde, Guinea Bissau, São Tomé and Príncipe and Their Diasporas. Lisbon: Hangar Books, 2021. https://hangar.com.pt/en/loja/atlantica-contemporary-art-from-cabo-verde-guinea-bissau-sao-tome-and-principe-and-their-diasporas/. Quotes available at ^return-colonial-pain-to-its-thinkers. ↩

-

CEsA – Centro de Estudos sobre África e do Desenvolvimento. Cooperação – Rota do Escravo. Accessed May 7, 2025. https://cesa.rc.iseg.ulisboa.pt/rotadoescravo/?page_id=12. Quotes available at ^colonial-period-as-tourism and The Contested Histories Initiative, Slave Market Museum in Portugal. Quotes available at ^museum-erasure. ↩

-

Lisbon Inaugurates Street Signs African History. A Mensagem. January 13, 2024. https://amensagem.pt/2024/01/13/lisbon-inaugurates-street-signs-african-history/. ↩

-

JMJ: Oeiras prevê gastar um milhão de euros com evento com Papa Francisco e voluntários. Expresso. February 15, 2023. https://expresso.pt/politica/2023-02-15-JMJ-Oeiras-preve-gastar-um-milhao-de-euros-com-evento-com-Papa-Francisco-e-voluntarios-ba690a38. ↩

-

in Padrão dos “Descobrimentos.” Accessed May 7, 2025. https://padraodosdescobrimentos.pt/. (Note: there is absolutely no reference to coloniality, violence or wrong-doing. This monument is seen as a major sightseeing point when visiting Lisbon as a tourist.) ↩

-

Peralta, Elsa. The Memorialization of Empire in Postcolonial Portugal: Identity Politics and the Commodification of History, Portuguese Literary & Cultural Studies 36-37 (2022): 156. https://ojs.lib.umassd.edu/plcs/article/view/PLCS36_37_Peralta_page156. Quotes available at ^vieira. ↩

-

Contested Legacies Portugal. The Early Atlantic Slave Trade in Portugal. Accessed May 7, 2025. https://contestedlegaciesportugal.org/ - “The most widely accepted interpretation of the street name Rua do Poço dos Negros suggests it being because it was the site of a pit holding the bodies of enslaved people of African origin. The little that we do know with certainty is that King Manuel I issued a royal law in 1515 complaining about dead bodies of enslaved people being abandoned in a dump in this area of the city. In that law he also ordered the City Council to build a pit in which these bodies should be thrown”. ↩

-

In Duarte, Mariana. Desmascarar o lado colonial do Porto: ‘o passado não passou’. Público. December 21, 2019. https://www.publico.pt/2019/12/21/culturaipsilon/noticia/desmascarar-lado-colonial-porto-passado-nao-passou-1898132, the author mentions several artifacts mentioned in the exhibition Unearthing memories. ↩

-

World of Discoveries. https://www.worldofdiscoveries.com/. Accessed May 7, 2025. (Note: An interactive museum about the maritime expansion catered to kids. The website has no reference to colonisation or violence whatsoever. In fact, in the corporate ethics section of the website, they claim: “At World of Discoveries, corporate ethics is not just a term; it is a commitment that governs all our actions and decisions. We are driven by a deep respect for our heritage, the community we serve and the responsibility to preserve and pass on the history of great discoveries with integrity and accuracy.”, “Integrity – We act with honesty and transparency, ensuring that the content we present is authentic and based on rigorous research.”, “Respect – We value the diversity and pluralism of historical narratives, approaching each story objectively.”, “This is a space where every opinion is valued and every voice is heard”.) ↩

-

Alves, Barbara. Turned into Stone - The Portuguese Colonial Exhibitions Today. PARSE. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://parsejournal.com/article/turned-into-stone-the-portuguese-colonial-exhibitions-today/. ↩

-

Peralta, Elsa. The Memorialization of Empire in Postcolonial Portugal. Quotes available at Expo 98 and the Memorialization of the Empire. ↩

-

Alves, Turned into Stone - The Portuguese Colonial Exhibitions Today Quotes available at ^elsaperalta2 and Turned into Stone - The Portuguese Colonial Exhibitions Today. ↩

-

Ibid. Quotes available at ^elsa-peralta1. ↩

-

Bastos, Cristiana, and Cláudia Castelo. Lusotropicalismo. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.1486. ↩

-

Wikipédia, a enciclopédia livre. Baltazar Rebelo de Sousa. Last modified March 28, 2023. https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baltazar_Rebelo_de_Sousa. ↩

-

Wikipedia. Slavery in Portugal. Last modified April 14, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavery_in_Portugal and Cartwright, Mark. Portuguese Empire. World History Encyclopedia. Last modified July 19, 2021. https://www.worldhistory.org/Portuguese_Empire/. As Cartwright notes ”(…) slaves continued to be imported to São Tomé and Principe until prohibition in 1908. Slaves were then replaced by African labourers who had to be repatriated after a certain number of years, but their living conditions were little different from those their slave predecessors had suffered”. This is evident through official government documents like Código do trabalho dos indígenas nas colónias portuguesas de África, and interviews conducted in Forced labour by those who lived through it. ↩

-

de Sousa, Vítor. As marcas do luso-tropicalismo nas intervenções do Presidente da República português (2016-2021).Revista Ciências Humanas 14, no. 2 (2021): 10–24. https://doi.org/10.32813/2179-1120.2121.v14.n2.a744. Quotes available at ^marcelo1, ^marcelo2, ^marcelo3, ^marcelo4. ↩

-

Peralta, Memorialization of Empire, 156. Quotes available at ^websummit. ↩

-

The first four would be the Assyrian, Persian, Greek, and Roman. ↩

-

Castanhede, Francisco, João Silva, Marília Gago and Paula Torrão. O fio da História - História | 8 ano. Texto Editores, 2022, 1-8 & 15-48. Available at História 8ano. ↩

-

Paiva, Ana, Bárbara Meireles, Gabriela Almeida and Sónia Junqueira. Palavra CHAVE 9 - Português | 9.0 ano. Porto Editora, 2024, 1-6 & 91-112. Available at Português 9ano. ↩

-

Kilomba, Grada. Memórias da plantação: Episódios de racismo quotidiano. Translated by N. Quintas. Lisbon: Orfeu Negro, 2019. Quotes available at ^memorias1. ↩

-

Camões, Luís. Os Lusíadas. 4th ed. Preface by Álvaro Júlio da Costa Pimpão. Presentation by António Castro. Instituto Camões, Ministério dos Negócios Estrangeiros, 2000. and Camões, Luís. The Lusiad; or, The Discovery of India. Translated by William Julius Mickle. 5th ed. Revised by E. Richmond Hodges. London: George Bell and Sons, 1877. Project Gutenberg (eBook). Accessed May 22, 2025. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/32528/32528-h/32528-h.htm. ↩ ↩2

-

Wilson, Catherine. France’s Colonial Strategy Blamed for Division in Troubled New Caledonia. Al Jazeera. August 1, 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/8/1/frances-colonial-strategy-blamed-for-division-in-troubled-new-caledonia and APA-Ouagadougou, Insult to All Africans: Macron Under Fire from Burkina Strongman. APA News. January 14, 2025. https://apanews.net/insult-to-all-africans-macron-under-fire-from-burkina-strongman/. ↩

-

*Associação dos Professores de História and Mariana Lagarto. Efeitos humanos e económicos da Guerra Colonial. RTP Ensina. Last modified 2021. Accessed May 15, 2025. https://ensina.rtp.pt/explicador/efeitos-humanos-e-economicos-da-guerra-colonial. ↩

-

Kedrosky, Davis, and Nuno Palma. The cross of gold, Brazilian treasure, and the decline of Portugal. CEPR: VoxEU. 2024. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/cross-gold-brazilian-treasure-and-decline-portugal. ↩

-

Director of Central Intelligence. The outlook for portugal. National Intelligence Estimate, Number 27.2-59. United States Intelligence Board. 1959. ↩

-

I use “decolonisation” in quotes, as neocolonial structures remain in place to this day, just like coloniality does. ↩

-

Reis, Bruno and Pedro Oliveira. The Power and Limits of Cultural Myths in Portugal’s Search for a Post-Imperial Role. International History Review, 2017, 1-23. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07075332.2016.1253599?journalCode=rinh20.* ↩

-

Mendy, Peter, Sa’eed Husaini. The Socialist Agronomist Who Helped End Portuguese Colonialism. Jacobin, 2019. Quotes available at The Socialist Agronomist Who Helped End Portuguese Colonialism. ↩

-

Reis and Oliveira. The Power and Limits of Cultural Myths in Portugal’s Search for a Post-Imperial Role. Quotes available at ^salazar. ↩

-

Lourenço, Eduardo. O Labirinto da Saudade: Psicanálise Mítica do Destino Português. 5th ed. Lisbon: Biblioteca Dom Quixote, 1978. ↩

-

in the verse “Cessem do sábio Grego e do Troiano” of stanza 3, canto I. ↩

-

Hegel’s definition of epic poetry privileges Greco-Roman and Western Christian models as the pure form of epic. Considering, for example Mahabharata, Ramayana, African griot traditions, oral epics (e.g. Ozidi Saga), as less developed or primitive, and justifying Europe’s “civilizing mission”. ↩

-

Hegel, Georg. Chapter 3 in Part 3, Section 3, of Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art. Selections from Hegel’s Lectures on Aesthetics, by Bernard Bosanquet & W.M. Bryant. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy. 1886. Translated by T. M. Knox. Marxists Internet Archive. Accessed May 19, 2025. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/ae/part3-section3-chapter3.htm. ↩

-

Lourenço, O Labirinto da Saudade. Quotes available at ^eduardo2. ↩

-

Glissant, Édouard. Poética da relação. Translated and revised by Marta Mendonça. Porto: Sextante Editora, 2011, 53-66. ISBN 978-972-0-07153-8. ↩

-

Glissant, Poética da relação, 11. on Rhizome - Gille Deleuze. ↩

-

Glissant, Poética da relação, 17-24. ↩

-

Martins, Mariana. references, ideas and techniques. 2024. https://gleaming-join-3fc.notion.site/references-ideas-techniques-2afd4af098b242eda61b21e4ab4bf33f. ↩

-

Redmayne, Isabella. Epic Echoes in Derek Walcott’s Omeros. Antigone Journal. April 20, 2024. Accessed May 22, 2025. https://antigonejournal.com/2024/04/derek-walcott-omeros/. ↩

-

Campagna, Federico. World-ing, or: How to Embrace the End of an Era. Mousse Magazine. September 17, 2020. https://www.moussemagazine.it/magazine/world-ing-federico-campagna-riboca2-2nd-riga-international-biennial-of-contemporary-art-2020/. ↩

-

Moreira, Schofield and Mónica de Miranda, TO DECOLONISE. Quotes available at ^return-colonial-pain-to-its-thinkers. ↩